Showing posts with label Japanese. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Japanese. Show all posts

Monday, July 9, 2012

fiddlehead tempura

Banner year of 1972. Blurred edges become lines that shift and shift until they steady and lay sharp. Sounds and colors begin to fill the space. I was ten that year. My toes bulged against the box of my shoes wanting to stretch out and see the bigger world beyond the canvas.

On a day I sat. Sometimes I'd sit doing nothing. What are you doing? they'd say. Nothing. What do you mean nothing? They said. Huh? Lions just lay there in the dirt of Africa when it's hot. Don't you sometimes sit and do nothing? Try it sometime. I'd sit sometimes on the the edge of the barn roof watching below the hang of the roof as goats crisscross the mud and head-bobbing chickens peck at the pebbles of the runway. So I'd have to come down eventually to pitch the hay. What do stinky animals understand of order? They understand musk. You cannot deny them their musk.

“Is that all of them, Marge.” I say. “You're not a border collie. Where’s Arnie?”

Corners everywhere are gray-blue. I wipe the sweat and it gets to be a little cold where I'm dripping. A ruddy flash goes, a coonhound from the blindside of the barn into the hay mound. He tosses up the stray hay as if a salad with his black nose and floppy ears and attacks the rest of the straw that abandoned systems of order raked in for hours.

“Stop it, Arnie! That’s my mess!” He bends his head to the side. His dark eyes are shiny. Some green at their edges. Colored corners too, like darkening sky. He seems to think I’m yelling at him praise and not just yelling at him. Marge runs back from cornering the goats and leaps into the crushed pile of the golds and yellows.

It seems memories are sharpest when the weather is clear or colored. The cold somehow preserves thoughts too. Out in the world beyond the unpainted palings I am no longer a child pretending to be a lion during summer in the serengeti where the painted underbrush is hidden and where cubs are likewise concealed where parts of an old world has passed along with parts of myself.

July 24, 1980

Steep blues reach low onto the ground. The sky still exists because we think of its existence. I cannot do more than fathom. There are many dark sweeps that come together to form the forest. There are piecemeal pines and there are dripping mists that sit sentinel against this last of the cobalt in their figures.

Arnie is against my lap as I lean against the lap of a redwood, ancient scaffolds against me and along the soil and mulch of needles surrounding. He is warm and somehow the base of the tree is warm, as if alive in the way of man. It is resinous and reminds me of my oily grandmother when she leans in to kiss me. He nudges deeper into my arms and I can feel his cold, wet nose. I want to whimper with him but just sniffle.

Where are they? Taking a number two cannot wait or so I told them and I told them to wait. But as any distracted photographer too fixed behind the viewfinder and not to their environs, they forget where they are, forget why they’re there at all, forget their charge of company, forget the other frames.

Maybe it was just me. Arnie and Marge had taken my side as I did my thing. I suppose such a thing is fair, since it was I that usually cleaned up after their number two. Marge got up first. She looked up and into that obscured shade between the narrows of trunk hulks betwixt giant red and black-green ferns and a bank of mist taking whatever shape that mists and shadows can draw together, becoming solid for the eyes only, or if you dared, for the touch, if you put your arm forth and walked into it without asking what's inside. With trowel I fill in the cat hole. It is easy to get lost, but I had sat looking back towards the direction of the trail. Marge’s nose was twitching and her ears and her jowls stirred up the currents of an invisible rainbow of odors to which only her dogginess was attuned. She follows.

“Margie!”

“Marge! Come!” She doesn't. She's on a scent. Sense over recall. The law of dogs.

Arnie does not yet give chase. He is a methodical one, like me. He waits for me to do my pants. And then we are both standing in the thick of nettles and broadleaves. Just standing there. Just standing. Just standing there.

July 25, 1980

Crepuscular dust live on the light and shadow. They push down below the branches like a many-hand god, some imagined sanctum for spiders and their spiderlings. In this universe the only evidence are cobwebs and unspeaking plants of unobserved histories and old old light from an unseen heaven.

I can yet still turn back. Now. Right now. The cardinal direction is still known. I could cross the trail if I move in that one arrowed path. All to save myself. My friends will come find me. I think this and I’m somehow reassured. My pastor would call it faith. Back then I did not know there was no god. No such thing. Maybe not even faith or the goodly things universal to man borrowed for religion. Faith was a word children understood though. And how I understood it was that somehow I would without doubt find my best friend of all, Marge.

July 26, 1980

We are standing like the very trees. I thought we all were? Rings rings rings. Grow taller each year. Grow inside each year. My stomach rumbles again and I think I’m hungry but I’m not quite sure about that either. There's a span of deadwood. Arnie does not hesitate. He does not understand pathogens. And if he did, he’d drink it all the same. I sip from the same seep flowing between a ditch carved between two redwoods. They stand as if brothers, as if Arnie and me. I once heard the same pastor tell about the story in where men are judged by how they drink from a pond, on their knees in subservience or in the way that Arnie does it, lapping with tongue and gusto. I’m glad to be judged among my best friends. There are none two nobler. I had aimed to prove it to whatever God thought dogs were filthy and wretched.

July 28, 1980

All I can think about is food. I enter another sanctuary. There is a natural coppice and here armies of sprouts shaped like violin heads furl towards the pillared light from the terraces of branches. I eat them by handfuls. I pause and look back and Arnie is laying his head on his paws with eyes wide open into the shadows behind the coppice. Can dogs think? I’m not sure. Even if they did, wouldn’t it all be in pictures? But if Arnie is awake, something is churning inside his dog head, but is that something beyond food?

I crawl around hunting for more fiddleheads. My knees and pants are soaked and sprent with fine grains of earth. If it’s to be a cold nightfall, I might not make it to morning. It seemed to get colder each night with less and less in my stomach. My hands freeze with two bright green fiddleheads. A bead of dew drips. My mouth hangs. Touching my knees are the outlines of an animal speaking a terrible silence that had once slept on a patch of young ferns that are now crushed so young and early. There is no body only an impression. Arnie brushes up against me before sniffing and encircling and finally laying down in the patch. He stares at me again with those dark thinking eyes. With outstretched hands I offer fiddleheads.

August 4, 1980

This log is not complaint of the life that I have lived. I write it simply to tell the world, my family, my friends, to all those curious at the nature of my existence, so that they needn’t be sad at my absence. Arnie and I loved you all and cherished all that this short life had to give.

P. S. Hope you have found/find Margie.

July 20, 1981

So soon I rushed back here when my parents found it right to fully entrust my life back to myself. Faith is something adults might not outgrow either. Faith engenders faith, and so, too, Arnie and I have the faith that perhaps Marge might find her way back home--to us.

We enter again that deepened glade that somehow diminished light can enter, feeding the forest of ferns their cosmic energy. By the tree skirting the coppice, the spot of that passed animal has sprouted into wild splendor and I can barely tell it is the same place save for the distinctive slaggy pine that marks it. There is nothing more. Plant growths. Old-growths and older growths. Green and forested things that carpet our footfalls. Faith does not entrust with answers. It's just there.

Twenty paces out, I turn around, for Arnie did not follow so loyally and unquestionably as he has always done. I look about.

“Arnie.”

“Arnie!”

“Oh, please, God, not this again.”

I sigh and roll my eyes. My breath is calming again. He has interred himself between the stalks of two giant red ferns. He’s “thinking” again. I kneel down and he whimpers as I pet him. Somehow I know. He won’t be leaving this place, this very spot.

Story by HVH, inspired by Where the Red Fern Grows by Wilson Rawls

labels: Japanese, Vegan, Vegetarian

Thursday, May 31, 2012

takenoko

This area around this time gets a green only plants know. Leaves that have known sunlight so bright and long throughout the spring, the lasting summer. When was I last here? Not since I was childless, wifeless, for a time, homeless. During those days career was a word I used to chase away while others chased it their youths. Perhaps it might have been I that pissed away the years. Let’s face it, most of us end up doing so. But only some of us regret it.

Where are my rotten kids? That's something parents get honest about phrasing and asking. Stare at these spearish overgrowths of bamboo long enough and your mind drifts off to some yonder time zone that cannot be retread. There's a son and a daughter sequestered to some unknown corner playing hide-and-seek inside the clearly marked boundaries of the “Do not trample, sensitive rhizomes,” posts. Here greens and wilds and quiet spaces are a resource like time and productivity and profit. Quiet spaces. I remember once when such things came so free and freely in my adopted country. We had congressionally designated wildernesses without constricting quota systems and any brave man or woman (or they both, together), ready for adventure could hitch a ride to the trailhead. No cars and expensive car maintenance needed! Just fetch out that finger and get into the passenger side or back and listen to the sauntering old tales of well-made travelers in their Synchros.

That one year, I was on assignment also in Zhejiang, near these parts, before there was ever a park. Who knew they would dedicate minor shrines to a plant once deemed too common to be considered noble. Too bad we couldn’t as well save the panda. It was autumn then just as the summer monsoons were fading away westward back towards that upthrust spine of the Himalayas separating India and China.

I had been living among a father, mother, and daughter, having my own bed raised up by bamboo, sitting in chairs made of bamboo, cooking with bamboo utensils, eating bamboo. Did you know you can boil water in bamboo? A saying runs in this region: if it has four legs and is not a table, or if it flies and is not a plane, we cook it. They had to them only the essentials, nothing beyond their family name and a few ragged shirts. For everything else the forest was their supermarket.

I bet men walked these banks millennia ago in footwear of bamboo. For those that didn’t, with a heavy load, they rode the wash of watercourse on bamboo rafts or skiffs, thrusting into the currents with poles of bamboo. And in their quivers, arrows made of the same. One bloodied, for the unfortunate one that met his end at the end of sharpened bamboo.

It was after the rat attack of 2061 that Min taught me how to write the character for bamboo using a bamboo brush on traditionally made bamboo pressed paper, scrolls, rather, from hardened dry strips. I studied the most critical stroke swiped so timidly across the paper. The gou lacked completeness. It is the stalks of the bamboo, two of them, zhu, that represent every possibly known bamboo permutation from this basic DNA.

“I don't understand. Why aren't you really angry? Why don't you go down and complain about. Your entire crop is gone. You have nothing to eat.”

He shrugged his shoulders and an eye. “Eh. What can you do?”

He seemed to note I was more upset with my sloppy calligraphy than his unwinnable case.

“You’re going to starve. You have to come to the city, find work.”

“I know that's what everyone else is doing. But we’ll be alright.”

“I don’t get you. It's like you don't even care. It's like you even revere the very thing that broke your farm.”

He let out a breath but it was not a sigh. He waved his arms and hands. A blush of bamboo grew and spread out of dark, wet ink.

A wise man said farmers were the first warriors. There was nothing ever truer than this in the case of Min. For months the bamboo surrounding the farm had been bursting of life and their stems clumping of flowers ready to set forth another generation of ancient culm at intervals only lucky men survive. This was not good for my mild hay fever. Walking a game trail nearby the house, there was more than the usual scurry of rats making their ways in between my legs and the stalks twice as tall as I. The sound of rats legion can be likened to a rushing stream. Min joined me and confirmed. These were not the rats that invaded his kitchen every dinner. They had bloomed alongside the flowering bamboo, timed to partake in this rare and choreographed explosion, just as Min’s family had done so for decades. This is how plants shared, without discrimination.

The rice fields did not see through to the fall. The carp needed the health of the rice fields to flourish. Their scaling bodies flushed down the muddied terraced fields. Black rats understand only obliteration. And yet Min found no virtue faulting anything, anyone. This is amusing since the only other species that can breed so aplenty are but humans. While not the usual crop of food, certainly, though, the people of the region had their fill of rats in their bellies for a season. And here I am, with two rats of my own.

I hear one of them through the forest as if a breeze. She sticks her head out from the foliage, her tiny hands barely able to part aside the emerald thickness.

“Dad, you gonna come play with us?”

I look at her, not saying a thing, trying to spot the whiskers.

If anything a grumble of curses. I turn around and start counting down.

When it takes a year in advance to reserve park space this precious, I’m not going to waste it brooding.

Story by HVH who is not a father--yet--perhaps ever.

labels: Japanese, Salad, Spring, Vegan, Vegetarian

Thursday, April 12, 2012

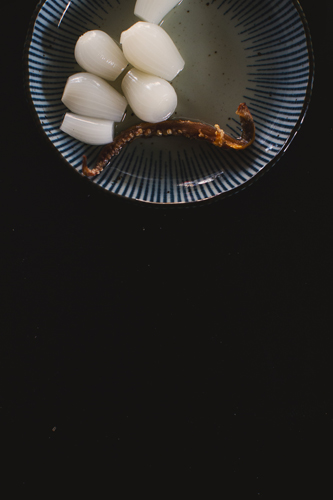

Surume and Rakkyo

Brine in the air. Fronds like a swarm broken upon the beach. Refuse that is manmade. One cannot escape refuse no matter the loneliest places. The thunder marching away. A wan light breaks through a thin lining, the last of it before leaving only the light of the moon. Hiroo walks along the beach letting the tides sweep his ankles. The crab doing likewise. At times the tide is stronger and cover the tops of the crab and when the tide sways the crab is gone.

He throws the green glass bottle into the sea. It will come back. Coconuts he keeps. Crabs. Fish if he can have it, but not upon the beach. Some flatfish and flounder get close to the shoals and sometimes he can hunt this but not this too gone a night. The storm had scared them gone. There's much more life on a island than one can see or know. It takes years to know. It is never an empty island. He doesn't have a shirt. Maybe it rotted off. Maybe it's kept somewhere. A cave. A hole. Gave it up to be like a coconut with coconut brown skin. In the tide pool, he catches a sun tempered and wrinkly man with a dangling beard staring back at him.

Not hungry. Just tired. So tired of crab and coconut water and rats and frail, bony birds, and garbage and sharks and sharp coral and roaches and sand fleas and salt water washing into his foot sores. I want fish but they are scared of me. The flatfish lay sleeping with their weirdly placed eyes and when I move to their sandy floor they rush to the other side of the island. They are clever with odd eyes. Maybe it's time again to go diving. When was that last? God. I don't want to remember. But god I'm so sick of everything else.

A freshly shaven spear of reed embellishes his left hand as his right hand draws through the swells and his well-worn feet kick him through the undercurrents and shimmering underworld. The living reef. The sea, the sea. The splash of many colored fish and their stripes and curious shaped fins. Their numbers and patterns kaleidoscopically painting against the slippery blue. The tubes of living plant-animal cinch valves and open their mouths and parse the density of the warm channel waters and take in nadir light. This is how it was before things were on land. Some of us missed the waters that we migrated back into the water. We shall always be closer than cousins on the tree.

Why have I been so frightened, so scared? The sharks are small and more mindful of me than I of them. Take a kill and take the fish blood and swim back onshore before they bite and eat you. The big ones.

Another deep breath. He dives. The floor is covered by ink. Is it even bottom? A phalanx of white and orange spiny lobsters spread where he is center. Wavy stones of brilliant coral and their edge a jungle of kelp. Faint light at all the edges. Before he reaches bottom the dark water feels thick. He can feel it move. Where is all the life? Only his now. He is alone again, differently alone than when ashore.

There are creatures born before the advent of time. Such things ancient cannot describe. This creature thumps inside all of us. We feel it dead center. There are things as old that live outside of us, too, in viscous darks, in places like jungles or watery trenches, where scratched snorkels cannot reach. The something moves. Tendrils. Water is whipped. Its eyes as bulbous as a cow’s. He breaches to the surface. Hacking salt water. Another eye. The sun glaring through the blanket of cumuli. He gasps. You can only swallow such much of the sea. The shoreline is a murmur in the backdrop of forever sea and sky. He splashes. Doesn't feel as if he's moving. The only sure thing is the earth moving, but you can't feel that. A hedge of palm heads wave but not towards his direction. The winds blow against him conspiring. Too far. I’ve wandered too far.

Once a book washed ashore and in this book lions wandered to the ends of their world defined by the weaving of the savannahs in their seasonal moods. Beyond this was the scrublands and this they too wandered, at times, postured into the domains of grit and gritty sands and thirst and elephants that have crushed them at the mud pools and watering holes. So much to run from, yet, the aurochs left prints that disappeared into the drifts and dunes that weaved and weaved until touching the sky. So they followed, for they were lions. At the end of the world, they looked long into the endless turquoise that they could not drink, their talon prints forever marked upon the white sands where they stood at last. But in the book it was an old man’s dream, and he too was becoming a man old of sorts.

He stares into the fire. The rich lobster meat sustained on a diet of coconut fills him but that is all it does. He stares long enough and his eyes burn but he does not blink. He chews blankly on the orange-red shell clean of brains and viscera.

White fish is adequate. White fish is boring. No, old man. You're tired. Of everything. Of white fish. Of everything. So tired. The hazy orange sun keeps him warm as he treads above the ocean proper. Appreciate being alive. No. Don't. Everything alive is alive. It's a very normal thing. So tired.

You want more than fish. Sometimes you want something and that's all there is to it. Did wanting bring a non-existence into being? No. Stop being stupid old man. Being alive doesn't guarantee wanting. Weren't you taught wanting is a disease? Yes. It's true. Being alive and then being not alive is a very normal thing. So tired of everything.

Adequate. And that is what, exactly? I don’t know. Why don’t you ask yourself. Aren’t I? Why are we talking amongst ourselves? That isn't a question, stupid old man. I pity us. Pity yourself, old man. I want dark fish that has blood as we do. Do as you must but beware. You can still swim back. Right now, you can still go back and be happy and alive.

The reed spear is nearly twice as long, reach as far as the monster’s. It is no assurance. Nothing in life is, and his heart tells him so loudly. Then he's gone and it's the only thing he hears.

In his wisdom he knows that the largest monsters, save for the whales, but they are hardly monsters, unlike the men that harpoon the calves and their mothers since time primordial, live far beneath what man can dive. Their’s is a world beyond darkness and light, for without one, without the other.

He floats through the inverted world of everything. He breaches and dives many times before getting adjusted. His lungs are primed. His heart. His heart. His heart. He is getting used to it all, the darkness, the unnameable things, if they have names yet, his pulse getting to a good tempo, and there's another strange thing and this thing he realizes it's moving as with intention and he knows it is the thing that is close to ancient as can be that lives outside of men but perhaps inside as well and is a real thing and here it is again. A tentacle slips around his leg and he lets a precious breath that bubbles from the black snorkel. Another slimy finger encloses him. He looks the beak implacable. The beak smiles.

From a pock of living rock a moray shoots out and latches with conviction and two-fold sawtoothed mouths a tentacle of the creature. He can breathe again but before he does he plunges the spear. Everything so inverted underwater. Things that are fast are slow. The heart is slow but is fast. The walker on land is slow in water. The fish quick in water is dead on land. The shaft of the green spear connects with the cow eye. The old man's head clears the horizon of water and air. The last that he saw, the thing's reach could have encompassed a fleet boat. He cannot shake the thoughts. Why are you still afraid? It's not dead. Just gone. The sun is warm. The water chills his toes.

From the high recess of the cave, safe from the tides that come and go, he stretches and touches. Fine-grained leather with a finer musk of mold. Aside the flickering of dead burning fronds and coconut husks, he opens the book to no passage in particular. A pamphlet is his bookmark and this he reads.

Come out, Hiroo. This is the order of your commander. The war is over.

He studies the flames like some confused water auger. They are orange and other colors among the black and the stars fixed in that substance and they reach down from the precipice of another world, perhaps one more wild than this island upon another. Are you still afraid, old man?

In the morning he gathered reeds and reeds. Trees and trees. Cordage and bark. Enough to make a ship. Or a very large, large fire.

Story by HVH

Monday, February 20, 2012

Gobo Peperoncino and Kinpira Gobo

Sodden ground. Muddy man laying there. Things uninvented: couch, convenience. He's earned his rest.

What he lives is his own nature documentary. No camera save what he sees himself. The grasses are stiff, amber. Along the riparian the end of chirpy businesses. The birds have started their night songs. Grasses and plants of the riverbanks array before him, a collection of food stuffs, not quite a meal. Neither words such as meal and family have been invented, yet he knows of their substance. He harvests from the land when time and season permit, eats it then and there if fire is unneeded. There is no ritual, no prayer. The ritual is with the people he eats with, more than the time and place and even the food. Sometimes there is no food so the prayer goes out of his mouth and than into it. That is the origin of dinner.

His gather ranges from big to small, slim to fat, juicy to possibly poisonous. Toxins can numb the tongue and if you were brave or stupid or just too hungry to care maybe your stomach gets knotted and you stop caring about food or anything and you just want to die, quickly. He knows them by shape, by features like limbs and growths. We know them as cattail, leek, fennel, lotus root, other less strange tuber, maybe potato, maybe, cucumber. He needn’t say wild, for they are all wild. He is wild and the same.

I have seen a few wild cucumbers myself on the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. They are small and scraggly and hardly a bite. They are like miniature daikon and white on the outside with specks of dirt that cling stubbornly. There’s a slight bitterness at the end, a perfect hint of green. They might have grown next to the wild onion. There's a kind of onion that is not an onion but in fact poisonous. So that's something I haven't tried because I'm not brave or stupid enough or an expert in these matters.

What does it mean when others describe a food as earthy? They taste of the earth? Of dirt? Well, that's what I ate. Dirt. But is that not unclean and soiled? That's how you know organic from other kinds of produce at the market. They are dirty. If they're not, they're imperfect. Or bruised. Or maybe that's just a way of being just right. Or have weird spots that you wish was dirt. Maybe they're organisms small and dead that have cycled through the layers of the ground that carry all our feet, all that has ever been on our tiny spot of island. It is more than sensations on your tongue and the feeling in your mouth and the satisfaction in the gut. But it is a feeling like some unspeakable nostalgia pointing directly to the firmament. You begin to understand earthy when you eat a part of the world. It’s a feeling that the cells of living food tells you. And they become a part of you, and they impart a heavy wisdom, though they are just plant fibers fashioned from the soil and the light of the sun.

The man spreads the bunch at the end of his arrayed collection. They are longish roots, longer than the others, as tall as his son that passed away last autumn. The flowers are gone, no telling what they might have looked like, and the leaves, shriveled and missing any green if there was ever any green. For the cattails have all shed their dandelion tops, spreading far and away by the wind. He wants to bite in but he knows better. Firstly, you break the skin of the plant. You rub it in yours. You wait for hours, maybe a day or so. You then lick it. Then you wait again. Don't die of starvation yet. Eat what you know for now. Then you bite a tiny morsel. You spit. Are you alright? Are you numb? Are you dead yet? Now you will take the leap. But roots are hard and hardy. He should not eat them uncooked. They can be acrid and will spoil the stomach for many days even if they won't kill you outright. A man feels human with a fire he made himself and he should have a fire while there's still light to cook by and to stave the edge of darkness away and maybe things in the outer dark.

He slices the tall, muddy root that resembles a carrot. It is soaked in the ribs of a wicker basket, hanging off the side of the flat river boat. The trembling stream runs past. He wonders if it will taste like lotus root or the strange other tubers he has grown fond for. The hare has been cleaned and spitted. He licks his lips and waits, watching the crackling of the fire. At the edge he is a flat figure.

My father and I have also made discoveries at water’s edge. We walked the drying creeks of a small town-city. Thinking back, I’m not sure why we made these hikes. No good reason save no reason which is always the best reason. But maybe it was it to teach me? About things that can only be learned through walks. There were wild gooseberries that flourished on its outskirts. He snatched them from the tall stalks that could easily be dismissed for another weed, outstretched his open palms. “Eat it,” he said. He only said. It was no command to obey. But I did not hesitate. I chewed while we watched each other. I did not say anything more. Neither he. I cannot remember if they were tart or sweet, and in what proportions, only that they were tiny, perfectly green, different and delicious, and perhaps a bit sticky. I remember only not saying. How did my father know these things that primitive man had to discover for himself? The same way. Walks. Walks. And sharing. He was a brass laborer, with a sixth grade education from a developing country. He could not tell you what a star was, or why they were pinned against the background of night, or knew how to read a Britannica or botanical field guide. And what were we doing re-enacting these men long gone when lanterned gooseberries could be bought for decoration (but not for food) at the store.

It was the same for the inventor of food that put burdock into the vernacular. Acts of courage, acts of desperation, acts of kindness. Acts. Acts. Acts IV and V. Has it become a dead language, though, one called back into the lexicon for purposes of romance. I dare not say that only in Asia is burdock called food. Anthropologists say that even ancient Britons harvested burdock. Britons that ate it alongside acorn meal spread flat upon gray slabbed stones on top still hot ashes and still burning coals gray on the outside with a little fire showing in between the break. The green revolution has taught us to grow things that grow more, faster. What can burdock feed? No industry. It's a side-note in a portfolio of food owned by one company to attract shopping carts meant to be filled with meatier things. What is mushroom to a person? To a man before the advent of civilization, to a man with nothing but? To the vegan it is the meat. To the first forager a taste of earth of the earth that animals eat, man, the animals, too. I say, put mushroom and burdock together. And hell, meat if you want.

And when you eat it you will know the taste of dirt. You will remember those backyard mudpies when you thought it was a good idea to eat mud. Use your imagination here, too. Burdock tastes like burdock, just as gooseberries taste like gooseberries, and the other white meat tastes like whatever it happens to be and not actually chicken. It's very special dirt. Nuanced or too strong for the picky eater. Then too bland for others. Refined palettes need unrefining. Obscurity will inform your vocabulary. It’s something worth trying many times, like good art, until gotten. The reward is the gobo itself. Understanding is.

Story by HVH

labels: Italian, Japanese, Vegetarian