Monday, February 11, 2013

Chai around India, Part Two

Colnago chai

A Colnago frame is lashed to the balustrade. The bike made a journey to get here. The one that comes to mind is not the one that led it up here into the loft of Kala Ghoda café.

It might have been born from a once small factory. It had ferried across continents through red, blue, and off-colored scratched shipping crates, carried on the backs of dirty trucks, settling finally on store racks. Or not so finally for the journey of a bicycle leaves respite forever a delusion. At some point someone takes it and gives it a home and journeys start anew.

Perhaps this home was one of a professional cyclist. Sojourns then fetched the rider towards serried horizons where one look made you feel so small. Rides that took him through the alp passes and empty roads for bad weather and wide ravines just below him and past villages in the countryside. All things are so wide and far and yet not so far on a bicycle, all time marked by the passing of things like stars like our star and seasons. On days fallen white with patches slaking all around, weather blew sideways but the bike did not. But there were also days with sun. On the first day of the training season, he had pulled on the short-sleeve jersey. The new route led beneath the shadows of tall poplars, slender birches, elder oaks. Then the shoulders of shade became dappled and then there was just sun unblinking. It would be a week before he could put on a long-sleeve.

One day came it is the hour of the race. The owner had sneered when it was suggested that he should ride the corporate sponsored bike of another breed. All parts new and 100% reliable A-Okay USA. Well, he'd none of that. Everything was replaced save the guts on the Colnago Beast, which he began to call it. Though, a Colnago, or any bike, does not have guts save that which comes from rider. His riding partner once called him lame for using “Beast.” They rode on that morning for some time and he said no word about it or anything else. The usual self. Can't talk into the wind. Even if you do, the wind carries it off. The talking was all the cycling and the pedaling, the paced breathing. They followed proper draft etiquette until a swift coast down-mountain brought them wheel-to-wheel as spokes spat tainted waters and thin rubber siped through the muck thickening. His back was still perfectly hunched, eyes transfixed into the distance of road tunneling into vision. “Everything is shit. It’s 'cause of me. Family's gone. Things I thought I wanted. You think I'm a monster? It’s not like I cry. I don’t feel sorry for myself ... just a little sad, about the world. Look at it. Look at the mountains. So sad. Not for me, the sad. I'm just sad, not an asshole. Let me tell you, this thing gets me ... up at 4am.”

That year, Colnago was very happy. As for the Beast, it made other tours the world over before the rider could no longer bear to lay eyes to it each passing time he entered and left the modern flat. Trophies had the wrong meaning and his collection was too much. He did not want what he had. The thing he wanted could not. It wasn't even a thing. The skeleton hung in the rafters sheltering the mites in the dust, and it came to him that such refuge was too small for him, some once figured equation involving man and soul of machine. He shook his head towards the high-vaulted ceiling where light occasionally broke through in a parallelogram and he sighed back down towards the reclaimed redwood floor from California. “One more tour, then, eh. How’s Asia? How's anything? Only one way to know.

So let’s find out.”

Café chai

The driver splashes through the art and museum district and pools of rain water. It’s the same morning though I can hardly believe it’s the same day. Driver looks at a yellowed paper on the visor, our cropped faces in the mirror, the scattered people outside with solid or patterned umbrellas cellophane to weird weather. There's water everywhere and we're thirsty somehow. Somewhere is the fragrance of chai or some other exotic liquid though the cab could be drowned at any wrong turn. It feels like circles. Maybe we're not quite lost. It was not the circle that it could have been.

Last night a lawyer and aspirant talent to be of film and dance, Anaka, and her auntie had hailed a tuk tuk just outside of a Goan hotspot, two floors occupied by the standard ambient western restaurant lighting that turns steak a medium-rare no matter how it was ordered. But this was not a steak house and rather it was filled with Indians. We had filled on bombil, dried and fried small fish, the self-same source of pungency that tweaked our noses as we passed over neighborhoods in the lee of sun of residential high-rises where the fish were put out to dry. Also on the menu, spicy prawns and mutton everything, though mutton in India is actually goat. I've heard this one before. Veal. Chilean sea bass. Rocky mountain oysters. And so forth. The one I hate the most is prawn. On the spread was biryani. This is Bombay, so we should wait until we head to Hyderabad before we try the real deal biryani, says Anaka. I inform her it can’t be as odd as the one served by us on all the flight services but Em is too polite to speak at length. Confucius and my grade school teacher advised that I should shut my mouth or else have my stupidity reaffirmed. Isn’t such admonition overly cautious, perhaps, even cowardly? Make it safely to old age with reputation intact and then what? They'd counter with it's about difference of culture, you imperialist. It's about group harmony. Try harmonizing with 80 grit sandpaper.

Anaka and the Auntie has stature, something to do with the brilliant lime sari draping their shoulders. Garments are the final layer. Em and I stand behind as to not interfere. They call the ear of a curbed tuk tuk and they agree on something real quick-like, something I could never do as a man, as a gringo in India. I find out later she was also testing his competency to get us back our hotel. I tell you now that he wasn’t.

So our driver, let’s call him Bob, slashes through the hazy neons of some bustling streets and then escape through corridors where signs are caricatures. Bob presses with city animal instincts in a waving wall anonymous drivers and passengers and random wanderers of the quadruped variety. Cows and goats and I’m pretty damn sure a horse without rider stand staring on the concrete shoulders and at times, children, running alongside the drainage beneath a bridge rumbling with the incessant passage of commerce and industrialization. No cardboard cutouts and tents in makeshift quarters of alleyways behind a stolen shopping cart like some metal-framed burro and a dumpster, but only for that single night. But those are images I’ve seen elsewhere in faraway cities, home, America. I see something else. Smiles of the children. I do not doubt it. The mothers are squatted and resign themselves. Elsewhere through the trip, I will remember the families that laid stake to corners of busy sidewalks, where children sleep during the day on the bare concrete, or only pretend to sleep, where we, pretend to look or do not look at all.

I swear we were here twenty minutes ago. I can still tell the place though the only light are the tuk tuk and cab and cycle armies and their headlight beams and pale lamps from concrete and tin and wooden shacks, where I’m pretty sure my modest collection of books at home would not fit. Waiting for the jam to unjam, these houses flank our right, and on our other, a man crosses the fields of of colored plastic, dark rubber, mud and tell-tale tracks of animal and man. His sandals wade through it all, carrying back a jug of water with a spout like an elephant’s.

You have come to India, why? Yes, for a wedding. And? What of Bombay? Are you getting in your kicks, you gaudy, fortunate, tourist asshole?

There are means of feeling like a greater asshole. There are means and there is much more to being than to feeling. Have I made a blunder by comparing poverty with authenticity? I can’t help but once seeing the very thing I’ve read so many times in Nat Geo on the matter of the 7 billion population Malthusian scenario that now I breathe it and it is forever scored.

Bob makes uncounted stops by vendors and other drivers curbed on their break, smoking, chatting, sitting idly, anything but sleeping, for that is something done during the safety of day. Now we figure he’s the one asking for directions. Thank Indra.

Thank bob.

You’d think what felt like an hour or eternity was long enough for the drive back to our rooms. An hour getting lost and it would take seemingly another to get unlost. We’ve stopped next to the lot of a hotel where the name hued in broken light against the backdrop of nothing else remarkable. We tell him politely yet sternly this is not it, though the name of the hotel in the broken sign bears some likeness. He gestures, “This is right, this is it.” Of course we wouldn't ourselves personally know where we stayed. How foolish. I control my rising voice but it's not easy. He’s unhappy. I know this though we don’t speak the same language. I began to acknowledge others around me again. There’s Em. She's not out of place. I feel nothing out of place with her. She’s calm as a monk. “As long as we refuse to get off this rickshaw, we’ll be fine.” Talking to myself again.

The hotel guy is bored and comes out to investigate this business in the center of his lot which will bring him likely none. The street corner of empty spaces of concrete overwritten by white lines and arbitrary stalls. Traffic does not come nor go. Not here. There is really nothing here. Darkened buildings with open windows where people might live. A family crammed into single room hovels. The pallid glow of a tv, perhaps. Three souls and another now. A jetliner like a lion above our heads. A jungle in more ways than one. The damp air of mangrove still hangs. The hour of midnight and thus a new day ticks closer and closer but it would still be far too far from morning. The while the highway thrumbing is miles away. Maybe this place is more restless than NYC NY.

Hotel guy calls the number on our hotel business card, replete with directions and a map on the back as useful as sanskrit. This is obvious since they “discuss” at length the meanings. “Yeah. Behind the big theater? ” I ask, perhaps a flicker of connection. He’s pointing at the big landmark drawn dead-center. There’s a name of a road and a cross street. Thanks a lot, Britain. At this point I realize that no one is speaking English save for me and Em. Certainly, Em’s phone is only good for dicking around on, and not so much that actually making a business call in the land of Vodafone, so thank Indra that a modest man can own his own frequency. Mine? I didn’t bring. It’s not a part of my everyday carry kit. It's the one thing I purposely forget as much as I can. And it's also called a dumb phone. Seriously, a dumb phone. Hotel guy reaches some understanding, some idea now, puts away his dumb phone. Bob has an inkling so says their lilting heads. I shrug and get into the tuk tuk. That’s enough. Let’s get on.

Bob is illiterate. He had only glanced at the business card. Hotel guy was there to rescue him from his own ignorance. Not that he did that much better. Bob is assuredly consigned to his fraying seat on the tuk tuk for who knows how long. Bob jerks the motor into turning and he heads off into the shadows for the light of the ramp and highway. Bob’s and most of the world’s crises can be resolved through a few things: books, clean water, and the uprising of women (through books) into the crust that their equals, men, dwell. Relieve scarcity of those three things in a society and you will have a first class one. Also, let those who worship worship their own gods of rain. Easier said than done.

Something more than wheels, tiny rubber tires (only three), compressed natural gas, and Bob’s clear determination yet scrunchy face will get us where we need to be. The puttering of the rickshaw’s tiny motor sound hilarious and inspiring. Kids would fall harder for it than that stupid blue talking train Thomas and his bullshit I-can-do attitude. I have my own confidence. My tour group consisting of my wife and non-speaking driver instill enough that there isn’t room for doubt. So what? What’s always the worse that can happen? A random maiming or mugging. We die now or inevitably when entropy reaches our doorstep in a many billion years. There will not be any form of intelligence left, if there is presently. So who gives a shit? Trucks. Trucks. Honk, Okay, Please? Bumblebee taxis. BMWs. Mercedes-Benz. Honda motorcycles. Really, really generic ones. Vespas? Dogs. Rickshaws of every stripe. The bodies of night coming out to work and play amid people who walk the streets without fear of being crushed outright. I’ve said it. India’s national pastime is in extreme sports, not cricket. Lights. So many. Not of the tawdry lights of a corporatized square in a world class city. Bright and dull headlights aiming into bodies ahead of us, into the distance at times as far and as fast as light can travel. Yellows, whites, tints in between according to the orchestration of energy.

Things pass so quickly. To this day, it all passed so quickly though we were unmoving at times. So still and it still passed so quickly and I can hardly remember that night that moment lest it was recorded somehow, and for that, Em did. She scratched in her journal at night. She snapped away during the light. Time always passes so steadily which is to say so damn damn quickly, that far too few things such as mutable memory and creatures as short-lived as man can avail meaning. All a memory now, clear only by color and sense. When the night passed on and it was nearly gone we reached that point of the city within the outer darkness, much like our universe, an inexplicable something physicists rather call dark matter. Well, here’s your dark matter.

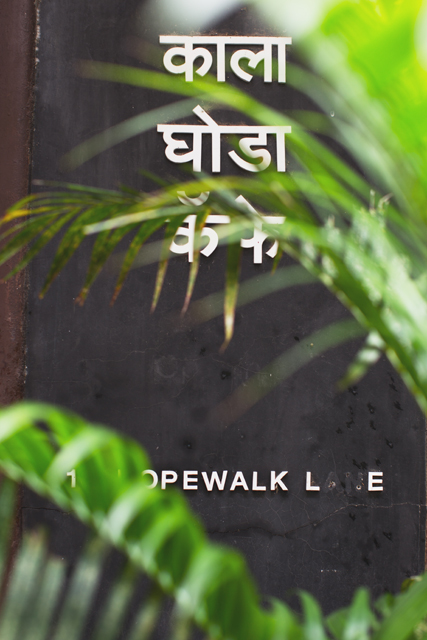

Morning in circles. We turn into a street occupied by kids and a ball’s trajectory. Sandals and shoes and puddles and rutted holes with a single ratty bat. A game of cricket. They eye us. Our windows down, they usher over out of curiosity or out of earnest want of helping some lost souls. They speak English. I smile, say, “Hi, guys. Kala Ghoda café? Should be on this street, yeah?”

“Yeah,” the kid of fifteen or so thinks aloud, surrounded by friends in the grayest white and brown stripes and holey brown or once ruddy shirts with unfading smiles or curious blankness. He thinks some more. “Over there, yeah.” The shorter and younger admire the wisdom of their ring leader.

I’m certain he had pointed a few directions. That's finger triangulation for you. We go. Thirty minutes later, we’re dropped off in a café or sorts, though not quite the one we sought. We take some sweet time to work out our fare and the driver drives off. We talk to a security guard in uniform light blue shirt and navy. Likely he is leading us astray again. We end up braving the city splashing of traffic and the slick sidewalks until we return to the cricket game between streets and cars and colonial stylized buildings in the tone of alabaster. Leaves and the unnaturally colorful debris of man scatter around the kids yelling and the muted crack of a battered swing. We walk. We walk.

The crackly blue walls at the back of a precinct. Trucks with an open backside made to carry guerilla fighters, who knows, and a modern police car. Two officers in uniform khaki topped by high-crowned official hats sit across from the other tending playing cards. Em wants to ask them for directions and I mumble but relent. They point down the corridor and say to turn and to continue.

No signs. Unremarkable storefronts selling things we’re not interested in buying. We pass a handful of these and come upon aged wooden doors flanked by potted fronds on either side. We’re too early so Em hangs back and takes her time to compose the scenery. I carry on and reach the crux of the intersection. A few blocks away I hear the main street abuzzing and swishing alive with mid-morning whirl of motors. Two women sit at the corner porch of their moldy building and knit something colorful in the early haze. A few steps away beneath a green awn a man buys cigarettes from a window. The street is big enough that a car or two might go through without getting stuck but I know this won’t happen soon. This is because a sickly dog sits smack center. He looks half sun-burnt but that is not his pain. He’s fending off the mites burrowing into his skin and perhaps the road traffic, too. All give him right of way and I stare a little while longer until the minutes turn the hour.

I look down the street and Em is gone. Walking back, I see she’s on a platform getting better angles on the morning’s drench still dripping around. Then someone opens the doors. They look so heavy like gates but they move so lightly. Behind that are perfectly clear glass ones as if they did not exist save for their beveled outlines and handles. We still wait. I wonder and ask Em if we had gotten here before anyone at all including the properly dressed young man inside arranging the details and likely starting the brew.

He unlocks the glass doors. A small place. Small means intimate. A retinue of tables and white chairs. A wall-bench of sorts rimming one side.

“Excuse me. What’s upstairs?”

“The loft. You can sit up there.”

“Yes, we would like that, please.”

Sure feel important. We head up unsure steps that would not accommodate every ideal 5’8” to 6’2” dark and handsome guy. I sit. Em gets the couch and both or all three seats. In my chair perhaps a renowned journalist from America or England or Australia once sat, dreaming up the same thing I was. To my right a Colnago frame is lashed to the balustrade.

Story by HVH