Showing posts with label Tea. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Tea. Show all posts

Friday, June 21, 2013

Chai around India, Part Three

Golden chai

New Delhi train conked on rails for 18 hours towards the border of Pakistan into lands of Jaisalmer. We sleep but not really. Time goes on. Things go by. Desert brush. Noiseless thoughts. Sometimes landscapes of nothingness. Nothingness is a hyperbole save for when describing death. Better to call it a still, sandy mirror. A rocky upthrust that looks like a misshapen mountain in the center of sand waves at us, everything else a blur in front of it. Isolated tents but not a single soul. Trains are strange. They take you forward. Wherever you sit on a train or wherever you stare, the tracks head away from home or towards someplace far off on a map or even home again, but they know only to push into the future, never going backwards.

Night turns away replaced by paleness through scratched window just as the timing for bird. I realize then that there are no songbirds. Another station stop. Concrete again, something like the day. Two men wipe a metal decanter on their haunches. A few women of unknown age go to their places. I don’t know where since there doesn’t seem be anything in sight other than the station facade. It’s cool, clear, clean, as a desert should be. Em and I have spent some time in the desert. At night the scorpions come out and the wind too, and then after midnight the cold, so that you forgot to move or sleep, and you would wake up before the sunrise without a clock. The feeling in the morning is clean, the surest word for desert we’ve learned.

“I think they’re going to be alright,” I tell Em. I know she knows this too yet we feel the concreteness of the day is and it is still early for how hot the sun is.

A droning gets louder. A man is calling out “chai garam chai garam chai garam chai.” We’re next to the door and he stops just before, as if a camel scoping out a waterhole, but it’s only us. Faded curtain shifts and we three stare. He seems mad but it’s only his tan and folded face of forty-something worked over by forty-something summers of sunshine.

“Chai????” His voice is chai-smooth.

“One please,” Em says with one finger up. Five rupees goes into his hand. Cheap and delicious, says Em. Cheap and real. Real cheap even. The chai wallah’s chai song we have not forgotten for when chai garam chai garam chai is involved in the course of day of our lives somehow, anyhow, small and pointless like a random smell that can’t be found when tried, we think of it and shall think of it always and laugh at how strange it was that it was only us he parted the curtains for, though he could not have seen behind it. Trains are strange truly.

Noon. Our station stop. Big Jaisalmer sign to assure everyone they’re not accidentally in Pakistan. Touts. People who can’t be trusted. Deals that are not such great deals if they lead into a ditch. A scrimmage of held signs outside the station advertising hotels. Palace. Free taxi. Swimming pool. One is a silver jeep and it’s ours. Our instant friend waits for no one else and we’re on the road.

“Someone tried to get us to stay at their place,” I say above the engine. “It’s like one-tenth of everything else here. Of course we thought it was a terrible idea.”

“You’re smart,” he says looking askance, eyes trained back to the dusty road again. Not impressed.

The view of the fort is staggeringly close. So this is how it feels to breathe India. Checking in. Bird perched on second floor window sill shade just outside our room. The colorful curtains swaying. You can see through them and see the sandy colors of the city outside.

Hotel chai to welcome us, to wet our mouths, lips, tongues, desires. Second order, to cure the queasiness in our guts. No, we’re not hungry, and thirsty no longer. Can’t even think about food. One of the brothers, the one that doesn’t smile, gives us his mobile and tells us to call.

“But it’s an international call.”

“That’s fine.”

No human answer. No human fingers that touched those machines in a long time. Em leaves a message on the machine for grandmother. She’s the type to overreact so that should take care of matters. She’ll cover all contingencies.

Booking another desert trip. Sojourns don’t stop for anyone, particularly when someone is down. No leverage to bargain against the serious brother’s kindness. It’s good then we’re not looking for bargains. We’re looking for things worth the cost.

We sit on the rooftop café and watch the fort and the people on rooftops carry on. I sit still but the sweat comes on. Nothing you can do about it. Just sit and sweat it out, sweat it all out. Evening comes closer but colors have not changed save for a small darkness overtaking the horizon.

“We’re going to ride to the Pakistani border,” says our guide the smiley brother. I jump on the back of the jeep and smile at his joke but then I see his own twisted smile and squinting eyes behind round sunglasses. The dusty afternoon cleared. Grey formations were moving in faster. They will move over the city and its last walls of defense that served only ancient empires but not this day.

“What’s today again?” I ask. Time and demarcations lost for weeks now. An hour on your wrist so pointless as schedules in Indian time.

“It’s today.”

“Ah, yes. And a hot day it is.”

“Going to be wet, too.”

Clouds scatter like toads. It stops pouring for a heartbeat. Brilliant desert light filters through. We make some stops. We get back in. We shuffle seats. We make stops. A fort for explorers and not warriors. A land shattered all around. An earthquake. A radioactive leak. Something that scared the residents away. We abandon the ghost heap of bricks and are back on the road. I volunteer for shotgun. Jeep windshield and sunglasses keep me from cold and blindness. Clouds return. Hanging onto the side I smile because there’s no door. Nothing to stop anything from coming inside. Nothing clearer than air between my eyeglasses and the scenery. My face is splashed though my smile is not washed away. If there were waterspots to dirty the view I couldn’t recall them.

The road lost like a ghost. Heavy wings hovering above our shoulders. It’s dark one minute then suddenly bright. Dusty and wet visions of a camel on the shoulder of the road or in a patch of barrenness surrounded by tufts of dried grass. One-lane road. Cars going either way. We see only trucks if cars at all. Thumping engines draws my mind back to New Delhi.

We have avoided yesterday but right now it comes back and can’t be pushed back.

“Dozo yoroshiku onegaishimasu,” I had said bowing.

“Something something something something,” my mother in-law said.

“Hai,” I bow, the only response to a face that’s trying not to reveal the stains of weakness. Saving face for the Japanese is everything. Em’s sister and mother head off towards the armed guard. We get into the taxi and I don’t look back not even at Em right beside me.

Our taxi driver who was commissioned for the day takes us to the train station. 1200 rupees. I give him 1500 and ask for change. He says I don’t have change. Of course. I began playing your game on the third day and that was weeks ago. I give him 1200 exact. He holds the 1000 bill to the sun with a serious eye, I see only his other. Is it real he asks. Of course it’s real. Seriously. Please. Go get it checked or not. Or take it. Sheesh. Fine, he says, smiling. I don’t know what that means but he’s taking it. Okay. Great. Grand. Fantastic. Bloody fantastic.

Security. Metal detector. Conveyer belt. Guy takes the ticket, pauses nonplussed. “Ummm … this is not the right station. See this? This says the old station not this station. This is the new one.”

I squint-stare at him and he seems an honest kid, but hell, ah hell, I snatch the ticket back. Em is horrified but follows me. We go inside the station. “Hey, hey! What are you doing! This is wrong station!” we hear the kid say but he can’t chase because he’s not riding anywhere.

A collection of people like debris waiting to board. We wait around and when we can’t wait we walk around. Our train has not flashed on the board. Where is it? I don’t know. Perhaps they’re slow. They’re not really sharp with schedules, you know. No. Look. The other trains have been posted and they’re around our time. Plus it’s only forty minutes or so. Doesn’t make sense. Let’s go upstairs. Yeah. Gaijin office.

The office is really busy. We are at the end of the queue which begins at the door which is as far as it can stretch, unless if you want to stand outside the office. Air conditioned. Lots of white people. The queue is spelled like Q. Just like that. A letter. A letter. I can think of another letter. F. F. F. F. F. S. S. S. S. Time is drawing nearer and there’s nothing to hold it back. If I could invent something to hold time back, to hold it still, to hold it forever in our hearts, I would be a filthy rich man in ways that money cannot touch with its dirtiness, then I would hold it forever in my heart, all the small, meaningless, terrible, rare, short, single moments with Em, with Kaze, even this one even though insecurity haunted. It could also be argued that a thing that knows death, but does not know of the hour and place, knows how to make art out of the finiteness of life. And so we wait. Wait. Time ticks and I hear it somewhere on the wall. I glance my watch. Yeah. Time. The times. These are the times. Hah!

Em goes to the corner where they’re not servicing anyone because we don’t need to book a ticket or to change our minds or times. We’re here, damn it. We’re here and that’s that. She comes back quickly.

This is the wrong station. Oh fuck are you serious? God I feel like such a prick to the kid now. And now I want to strangle that bad, bad man.

Radio taxi because the meter works and meters don’t negotiate very well or at all really. I try not to look at the watch but watch instead the meter. Oh well. I stare outside. The walls of the Red Fort go on and on. We did not go there. No worries. We’ll go next time. There’s no next time, silly. You say next time and even if you return to the very same spot the spot may be different somehow. That spot is of a different time now. It is not the same, nor will it ever be. That spot is of the next time spot and not of the now spot. Stop yourself when you say next time. There is no next time. Not ever. Next time is a thought for when you’re living in the now but you’re forgetting to. Now is next time already. Time is the fair man’s currency, 86,400 seconds a day. Hear the words of Joseph John Campbell. Eternity is now.

Driver wants 20 extra rupees on top of the fare. “This is a radio taxi,” I say, not that he needs reminding. “My god this is why I hate New Delhi.” He freaks out and apologizes. Listen, driver man, twenty rupees is such chump change I can’t even begin to express to you how much so save to tell you that my father used to break shit in ape-shit anger and destroyed anything in sight of value including my Transformers and G.I. Joes and my porcelain eight-year old ass. Because he felt like it. Now, driver man, had you just asked up front kindly, that would have been different and varying on my mood it might have been better for us all. But what you’re doing is called the fine print in America and that shit is ultra-terrible, even in America. Really, just plain awful. Bad American culture. Bad. Also, eff relativism.

Mcdonald’s. Mcdonald’s is the cleanest area in the old train station. Lights. Middle-class patrons. Indians. Security guard. Inside the Mcdonald’s they’re serving traditional chaat at a counter but it’s not a part of McDonald’s just inside of it, whatever that means. Strange. Maharaja mac sandwich. Strange. Ice in the coke. Oh well. Next door are the restrooms but when you went inside it became a wet prison cell and you forget to breathe. Strange and at times scary.

Outside in the real world again we go to the platforms and look for the boarding sheet with the listed passengers to verify that it’s ours and the cars they’re assigned. Ten minutes until departure. Across the concrete we see two hysterical Japanese. Their eyes are frantic through the crowds.

“Em. Those two look like your mother and sister.”

“Oh my god. What are they doing here?”

We’re already running towards them and see us and close the gap. They begin to talk and won’t stop and they start to cry in between the words. Em takes off her pack and pulls out her passport and trades off with her mother. I don’t understand a thing beyond the switcheroo. It’s all Japanese. A guy steps into the circle of a circus now, just random people trying not to help exactly but trying to find out what’s going on just the same. I don’t care. At some point I thank the guy because he has apparently got our mother and sister this far from the airport and their English is flimsy. I’m holding him and Ro. It’s all I can do. Then when I’m talking to Em again he and mother and sister are running up the stairs and are gone. Twenty minutes or so until their flight departure. Impossible.

“Can we do anything?” I say.

“We have to catch the train. We can’t miss it or it’ll be worse.”

And I know she’s right but by god, it still feels like betrayal, cowardice, selfishness, all wrapped into tight tinfoil and steamed. We still haven’t figured out which cars are which because the bluish gray paint are peeling the pale beige numbers are going with it and the train is long, long.

“AC2 are those down there,” a young European girl says. “Okay? Do you understand?” She thinks we’re mute, scared to talk, or don’t know a lick of English.

“Okay. Thank you so much.” Still not thinking. Just knowing that we owe a lot more.

The seats are facing an empty gray wall. We sit. The train hurtles into the future. There was nothing we could do to stop it.

Spin your head out here and there is nothing. Yet nothing is something here. Recall death, and even that is something. Nothing in the way that utility and phone lines have, poles and trees of artifice that keep civilization civil. Heavy white clouds textured like focaccia. The sky is all one cloud or it’s just pure sky and there’s nothing in it save dullness. The camels clop through the sandiness sticking to anything flat. If it sticks long enough they become hills. Some come into view. Dunes and ridges. Lines that curl. Yellowed grass between abutments. Branches and thorns. The caravan master in a brown light gandora whisks ahead and pulls a slender twig. He strips the dirt and the imperfections and tests it with a thwack-thwack. We can see into the far corners of the world and smell not trace of it. We hear only voices and they carry a short ways and are left softened with each passing step.

The sand is deep in parts and the caravan master breaks the steady sifting of camels by a light whack-whack. The camels surge ahead and you have to hold on or you’ll fall off the wrong side and no one’s gonna go back to get you, or so you fear. There’s a moment when my Yuin PK3s tell me something. Hooves are sprinting across the clear towards the next stable ground and the gray skies wince a little and a little rain drizzles on everything and I hear Sorma, Gumbalo, from their Mirage of the East. I remember the perfection of everything, and perfection is not something I believe, the smell of my wet white shirt and the dung and the static in the air and the stillness though the procession of the singleness of clouds and the heaviness of Sorma in my ears and Em ahead of me, just her back and blue-blue-desert-orange sari. And I remember thinking My god, if you lived here, you could come out into the desert every day. My god, if you lived here, you would live in a desert every day. Your jeep and feet and, if you could fit another dog into India, best friend and your best friend dog would be enough, more than what could ever fit into one small heart in the cornerless world that is India.

The caravan stops and this is where those who will sleep beneath the stars tonight stay but there won’t be any heavens seen. First order, boil water for chai. My god, the finest chai in all of India. My god, the finest chai in all of India. My my my my my. The gods. Chai.

I finish and put down the metal cup into the sand and watch the British couple walk and become smaller beneath a rainbow that had broken out above the dunes. Colors I had forgotten. Colors of all the dyes of cloth and people that wore them and their smiles and strange stares that had brushed by Em and I for a month as a gradient memory. And I remember thinking with certain smugness, My god, Hollywood, you cannot manufacture a better timed romance, so don’t even try. Don’t even try.

THE END

Story by HVH

Monday, February 11, 2013

Chai around India, Part Two

Colnago chai

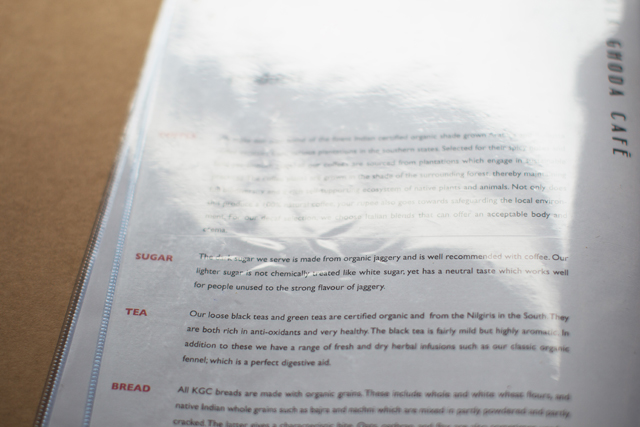

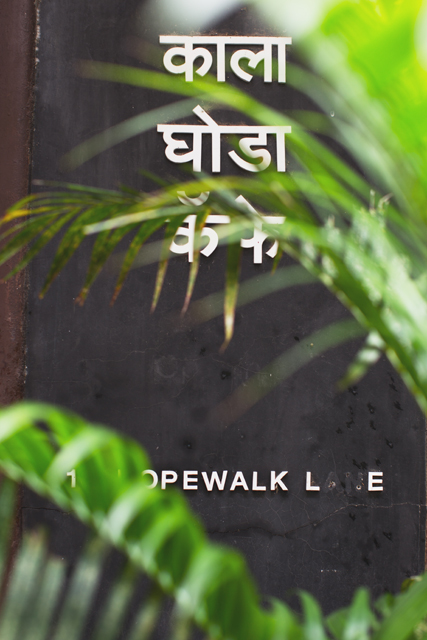

A Colnago frame is lashed to the balustrade. The bike made a journey to get here. The one that comes to mind is not the one that led it up here into the loft of Kala Ghoda café.

It might have been born from a once small factory. It had ferried across continents through red, blue, and off-colored scratched shipping crates, carried on the backs of dirty trucks, settling finally on store racks. Or not so finally for the journey of a bicycle leaves respite forever a delusion. At some point someone takes it and gives it a home and journeys start anew.

Perhaps this home was one of a professional cyclist. Sojourns then fetched the rider towards serried horizons where one look made you feel so small. Rides that took him through the alp passes and empty roads for bad weather and wide ravines just below him and past villages in the countryside. All things are so wide and far and yet not so far on a bicycle, all time marked by the passing of things like stars like our star and seasons. On days fallen white with patches slaking all around, weather blew sideways but the bike did not. But there were also days with sun. On the first day of the training season, he had pulled on the short-sleeve jersey. The new route led beneath the shadows of tall poplars, slender birches, elder oaks. Then the shoulders of shade became dappled and then there was just sun unblinking. It would be a week before he could put on a long-sleeve.

One day came it is the hour of the race. The owner had sneered when it was suggested that he should ride the corporate sponsored bike of another breed. All parts new and 100% reliable A-Okay USA. Well, he'd none of that. Everything was replaced save the guts on the Colnago Beast, which he began to call it. Though, a Colnago, or any bike, does not have guts save that which comes from rider. His riding partner once called him lame for using “Beast.” They rode on that morning for some time and he said no word about it or anything else. The usual self. Can't talk into the wind. Even if you do, the wind carries it off. The talking was all the cycling and the pedaling, the paced breathing. They followed proper draft etiquette until a swift coast down-mountain brought them wheel-to-wheel as spokes spat tainted waters and thin rubber siped through the muck thickening. His back was still perfectly hunched, eyes transfixed into the distance of road tunneling into vision. “Everything is shit. It’s 'cause of me. Family's gone. Things I thought I wanted. You think I'm a monster? It’s not like I cry. I don’t feel sorry for myself ... just a little sad, about the world. Look at it. Look at the mountains. So sad. Not for me, the sad. I'm just sad, not an asshole. Let me tell you, this thing gets me ... up at 4am.”

That year, Colnago was very happy. As for the Beast, it made other tours the world over before the rider could no longer bear to lay eyes to it each passing time he entered and left the modern flat. Trophies had the wrong meaning and his collection was too much. He did not want what he had. The thing he wanted could not. It wasn't even a thing. The skeleton hung in the rafters sheltering the mites in the dust, and it came to him that such refuge was too small for him, some once figured equation involving man and soul of machine. He shook his head towards the high-vaulted ceiling where light occasionally broke through in a parallelogram and he sighed back down towards the reclaimed redwood floor from California. “One more tour, then, eh. How’s Asia? How's anything? Only one way to know.

So let’s find out.”

Café chai

The driver splashes through the art and museum district and pools of rain water. It’s the same morning though I can hardly believe it’s the same day. Driver looks at a yellowed paper on the visor, our cropped faces in the mirror, the scattered people outside with solid or patterned umbrellas cellophane to weird weather. There's water everywhere and we're thirsty somehow. Somewhere is the fragrance of chai or some other exotic liquid though the cab could be drowned at any wrong turn. It feels like circles. Maybe we're not quite lost. It was not the circle that it could have been.

Last night a lawyer and aspirant talent to be of film and dance, Anaka, and her auntie had hailed a tuk tuk just outside of a Goan hotspot, two floors occupied by the standard ambient western restaurant lighting that turns steak a medium-rare no matter how it was ordered. But this was not a steak house and rather it was filled with Indians. We had filled on bombil, dried and fried small fish, the self-same source of pungency that tweaked our noses as we passed over neighborhoods in the lee of sun of residential high-rises where the fish were put out to dry. Also on the menu, spicy prawns and mutton everything, though mutton in India is actually goat. I've heard this one before. Veal. Chilean sea bass. Rocky mountain oysters. And so forth. The one I hate the most is prawn. On the spread was biryani. This is Bombay, so we should wait until we head to Hyderabad before we try the real deal biryani, says Anaka. I inform her it can’t be as odd as the one served by us on all the flight services but Em is too polite to speak at length. Confucius and my grade school teacher advised that I should shut my mouth or else have my stupidity reaffirmed. Isn’t such admonition overly cautious, perhaps, even cowardly? Make it safely to old age with reputation intact and then what? They'd counter with it's about difference of culture, you imperialist. It's about group harmony. Try harmonizing with 80 grit sandpaper.

Anaka and the Auntie has stature, something to do with the brilliant lime sari draping their shoulders. Garments are the final layer. Em and I stand behind as to not interfere. They call the ear of a curbed tuk tuk and they agree on something real quick-like, something I could never do as a man, as a gringo in India. I find out later she was also testing his competency to get us back our hotel. I tell you now that he wasn’t.

So our driver, let’s call him Bob, slashes through the hazy neons of some bustling streets and then escape through corridors where signs are caricatures. Bob presses with city animal instincts in a waving wall anonymous drivers and passengers and random wanderers of the quadruped variety. Cows and goats and I’m pretty damn sure a horse without rider stand staring on the concrete shoulders and at times, children, running alongside the drainage beneath a bridge rumbling with the incessant passage of commerce and industrialization. No cardboard cutouts and tents in makeshift quarters of alleyways behind a stolen shopping cart like some metal-framed burro and a dumpster, but only for that single night. But those are images I’ve seen elsewhere in faraway cities, home, America. I see something else. Smiles of the children. I do not doubt it. The mothers are squatted and resign themselves. Elsewhere through the trip, I will remember the families that laid stake to corners of busy sidewalks, where children sleep during the day on the bare concrete, or only pretend to sleep, where we, pretend to look or do not look at all.

I swear we were here twenty minutes ago. I can still tell the place though the only light are the tuk tuk and cab and cycle armies and their headlight beams and pale lamps from concrete and tin and wooden shacks, where I’m pretty sure my modest collection of books at home would not fit. Waiting for the jam to unjam, these houses flank our right, and on our other, a man crosses the fields of of colored plastic, dark rubber, mud and tell-tale tracks of animal and man. His sandals wade through it all, carrying back a jug of water with a spout like an elephant’s.

You have come to India, why? Yes, for a wedding. And? What of Bombay? Are you getting in your kicks, you gaudy, fortunate, tourist asshole?

There are means of feeling like a greater asshole. There are means and there is much more to being than to feeling. Have I made a blunder by comparing poverty with authenticity? I can’t help but once seeing the very thing I’ve read so many times in Nat Geo on the matter of the 7 billion population Malthusian scenario that now I breathe it and it is forever scored.

Bob makes uncounted stops by vendors and other drivers curbed on their break, smoking, chatting, sitting idly, anything but sleeping, for that is something done during the safety of day. Now we figure he’s the one asking for directions. Thank Indra.

Thank bob.

You’d think what felt like an hour or eternity was long enough for the drive back to our rooms. An hour getting lost and it would take seemingly another to get unlost. We’ve stopped next to the lot of a hotel where the name hued in broken light against the backdrop of nothing else remarkable. We tell him politely yet sternly this is not it, though the name of the hotel in the broken sign bears some likeness. He gestures, “This is right, this is it.” Of course we wouldn't ourselves personally know where we stayed. How foolish. I control my rising voice but it's not easy. He’s unhappy. I know this though we don’t speak the same language. I began to acknowledge others around me again. There’s Em. She's not out of place. I feel nothing out of place with her. She’s calm as a monk. “As long as we refuse to get off this rickshaw, we’ll be fine.” Talking to myself again.

The hotel guy is bored and comes out to investigate this business in the center of his lot which will bring him likely none. The street corner of empty spaces of concrete overwritten by white lines and arbitrary stalls. Traffic does not come nor go. Not here. There is really nothing here. Darkened buildings with open windows where people might live. A family crammed into single room hovels. The pallid glow of a tv, perhaps. Three souls and another now. A jetliner like a lion above our heads. A jungle in more ways than one. The damp air of mangrove still hangs. The hour of midnight and thus a new day ticks closer and closer but it would still be far too far from morning. The while the highway thrumbing is miles away. Maybe this place is more restless than NYC NY.

Hotel guy calls the number on our hotel business card, replete with directions and a map on the back as useful as sanskrit. This is obvious since they “discuss” at length the meanings. “Yeah. Behind the big theater? ” I ask, perhaps a flicker of connection. He’s pointing at the big landmark drawn dead-center. There’s a name of a road and a cross street. Thanks a lot, Britain. At this point I realize that no one is speaking English save for me and Em. Certainly, Em’s phone is only good for dicking around on, and not so much that actually making a business call in the land of Vodafone, so thank Indra that a modest man can own his own frequency. Mine? I didn’t bring. It’s not a part of my everyday carry kit. It's the one thing I purposely forget as much as I can. And it's also called a dumb phone. Seriously, a dumb phone. Hotel guy reaches some understanding, some idea now, puts away his dumb phone. Bob has an inkling so says their lilting heads. I shrug and get into the tuk tuk. That’s enough. Let’s get on.

Bob is illiterate. He had only glanced at the business card. Hotel guy was there to rescue him from his own ignorance. Not that he did that much better. Bob is assuredly consigned to his fraying seat on the tuk tuk for who knows how long. Bob jerks the motor into turning and he heads off into the shadows for the light of the ramp and highway. Bob’s and most of the world’s crises can be resolved through a few things: books, clean water, and the uprising of women (through books) into the crust that their equals, men, dwell. Relieve scarcity of those three things in a society and you will have a first class one. Also, let those who worship worship their own gods of rain. Easier said than done.

Something more than wheels, tiny rubber tires (only three), compressed natural gas, and Bob’s clear determination yet scrunchy face will get us where we need to be. The puttering of the rickshaw’s tiny motor sound hilarious and inspiring. Kids would fall harder for it than that stupid blue talking train Thomas and his bullshit I-can-do attitude. I have my own confidence. My tour group consisting of my wife and non-speaking driver instill enough that there isn’t room for doubt. So what? What’s always the worse that can happen? A random maiming or mugging. We die now or inevitably when entropy reaches our doorstep in a many billion years. There will not be any form of intelligence left, if there is presently. So who gives a shit? Trucks. Trucks. Honk, Okay, Please? Bumblebee taxis. BMWs. Mercedes-Benz. Honda motorcycles. Really, really generic ones. Vespas? Dogs. Rickshaws of every stripe. The bodies of night coming out to work and play amid people who walk the streets without fear of being crushed outright. I’ve said it. India’s national pastime is in extreme sports, not cricket. Lights. So many. Not of the tawdry lights of a corporatized square in a world class city. Bright and dull headlights aiming into bodies ahead of us, into the distance at times as far and as fast as light can travel. Yellows, whites, tints in between according to the orchestration of energy.

Things pass so quickly. To this day, it all passed so quickly though we were unmoving at times. So still and it still passed so quickly and I can hardly remember that night that moment lest it was recorded somehow, and for that, Em did. She scratched in her journal at night. She snapped away during the light. Time always passes so steadily which is to say so damn damn quickly, that far too few things such as mutable memory and creatures as short-lived as man can avail meaning. All a memory now, clear only by color and sense. When the night passed on and it was nearly gone we reached that point of the city within the outer darkness, much like our universe, an inexplicable something physicists rather call dark matter. Well, here’s your dark matter.

Morning in circles. We turn into a street occupied by kids and a ball’s trajectory. Sandals and shoes and puddles and rutted holes with a single ratty bat. A game of cricket. They eye us. Our windows down, they usher over out of curiosity or out of earnest want of helping some lost souls. They speak English. I smile, say, “Hi, guys. Kala Ghoda café? Should be on this street, yeah?”

“Yeah,” the kid of fifteen or so thinks aloud, surrounded by friends in the grayest white and brown stripes and holey brown or once ruddy shirts with unfading smiles or curious blankness. He thinks some more. “Over there, yeah.” The shorter and younger admire the wisdom of their ring leader.

I’m certain he had pointed a few directions. That's finger triangulation for you. We go. Thirty minutes later, we’re dropped off in a café or sorts, though not quite the one we sought. We take some sweet time to work out our fare and the driver drives off. We talk to a security guard in uniform light blue shirt and navy. Likely he is leading us astray again. We end up braving the city splashing of traffic and the slick sidewalks until we return to the cricket game between streets and cars and colonial stylized buildings in the tone of alabaster. Leaves and the unnaturally colorful debris of man scatter around the kids yelling and the muted crack of a battered swing. We walk. We walk.

The crackly blue walls at the back of a precinct. Trucks with an open backside made to carry guerilla fighters, who knows, and a modern police car. Two officers in uniform khaki topped by high-crowned official hats sit across from the other tending playing cards. Em wants to ask them for directions and I mumble but relent. They point down the corridor and say to turn and to continue.

No signs. Unremarkable storefronts selling things we’re not interested in buying. We pass a handful of these and come upon aged wooden doors flanked by potted fronds on either side. We’re too early so Em hangs back and takes her time to compose the scenery. I carry on and reach the crux of the intersection. A few blocks away I hear the main street abuzzing and swishing alive with mid-morning whirl of motors. Two women sit at the corner porch of their moldy building and knit something colorful in the early haze. A few steps away beneath a green awn a man buys cigarettes from a window. The street is big enough that a car or two might go through without getting stuck but I know this won’t happen soon. This is because a sickly dog sits smack center. He looks half sun-burnt but that is not his pain. He’s fending off the mites burrowing into his skin and perhaps the road traffic, too. All give him right of way and I stare a little while longer until the minutes turn the hour.

I look down the street and Em is gone. Walking back, I see she’s on a platform getting better angles on the morning’s drench still dripping around. Then someone opens the doors. They look so heavy like gates but they move so lightly. Behind that are perfectly clear glass ones as if they did not exist save for their beveled outlines and handles. We still wait. I wonder and ask Em if we had gotten here before anyone at all including the properly dressed young man inside arranging the details and likely starting the brew.

He unlocks the glass doors. A small place. Small means intimate. A retinue of tables and white chairs. A wall-bench of sorts rimming one side.

“Excuse me. What’s upstairs?”

“The loft. You can sit up there.”

“Yes, we would like that, please.”

Sure feel important. We head up unsure steps that would not accommodate every ideal 5’8” to 6’2” dark and handsome guy. I sit. Em gets the couch and both or all three seats. In my chair perhaps a renowned journalist from America or England or Australia once sat, dreaming up the same thing I was. To my right a Colnago frame is lashed to the balustrade.

Story by HVH

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Chai around India, Part One

07:19am

First sketches of Mumbai. Blue sky unseen. I know it’s blue because the sky is invariably so. Whether you sleep or are alive or dead, whether you look or don't look, maybe you don't even have eyes, maybe you can't even read this, the sky just is. It just is. Left or right, right or wrong, it’s just blue. Yet this morning, Indian skies tells me that the sky has always been a shade of gray or slate swaying in degree beneath the clouds. Of another blue, tarps and tarps stretch over boxes and boxes with open doors and windows inviting in the very black. These seem to me like the playhouses my friends and I hoisted up in our backyards, of cardboard and rotten wood and stolen 2x4s. No signs of life. There is more to conviction than what lies in sight. I know there are people, people like you and me, sleeping, dreaming, living, being, inside. The plane skids safely down though a skin of water washes over the field of tarmac. This is not one mile from the blue houses of tarp near the runway. Maybe they don't dream, only ask for quiet.

07:28am

India day two. Hotel chai. Dispensed from a biggish cylinder of metal. Lab experiment? Already mildly sweetened and creamed. Fresh ginger? Seems so. I can taste the bits. Why do they offer packets of sugar?

05:30am

Another day. Another morning. Sure could use some sleep or drugs. Caffeine would be nice. Streets are washed clean again. Streets swept of urine and whatever else. There’s a constant stench. If you opened your eyes or ears or other things in your city no matter how large not matter how small, you'd smell it the same. Some hide it better than others. But constant is the same. People often misuse the word constant. Sometimes they mean consistent, or every so often, or repeatedly, or continuously even, but rarely constant. But this is constant. It’s the smells I remember most. Rarely elsewhere do I either recall talk of the smells and you can’t smell through a guidebook. You can't smell through a TV either. The breath and perspiration of people being recycled by people. A rotting air of mangrove lingers across the view.

Cab windows partly down. I watch the private slushing through the forsaken streets. The other cabbies and the road tenant armies of tuk tuks have gone to rest. Their pitter-patter now no more than the soft drizzling of rain. Passing over the flyover reveals below a shanty town in the tremendous shadow of the bridge. A horde of bumblebee-colored cabs hunch together waiting out the last of night and rain. If they sleep here, in this city, properly called Bombay and not that political fiasco they have labeled as Mumbai, that must mean that the streets of NY also rest. And so we must all eventually.

07:20am

The light is out. So are clouds. The city is a softbox. No rain yet. Textures of people and walls and puddles are reflections of reflections. We wander past people buying twigs for teeth cleaning, this the vendor mimes to our curious stares. I am reminded of how the Native Americans who use creosote to do the same. Whose idea was it? Anyhow, it’s better than disposable toothbrushes.

Men in suits. Men in work clothes. Brown, blue, black. Young and old. Motorcycles. They go by us in no hurry. They don’t seem to care about what we’re doing. Don’t seem to care who we are. I’m standing in the middle of it all trying to assign a color and bit depth to the vertical bed of lichen or moss glowing brightly mineral, growing on a side of fallen brick against a nearly fallen wall in an alley. These are old places. Perhaps the Raj once called it theirs. Old and slow so that slower life can take root even if its in the city. Em is waiting for the condensation to evaporate from her ultra-wide lens. We have no idea where we are either, but this does not bother us. We’re delusional in our safety, or Indians, even of the city breed, are the most hospitable in ways they aren’t aware.

A few streets down and a few turns later, an intersection arises from the strange hush of the morning maze. The six way hub is a pulse of the city and it is alive and awake and confusing. To my left are high-rise apartments. Water spouts pour out a glacial valley-sized cataract of rain water. I think of all the pigeons nesting on the roof and their runoff. To our right, a vendor has pots of various sizes and heights boiling on rickety stoves. A few men in sit and stand nearby, sipping from their clear plastic cups and tall glasses. They stare back at us staring.

“I’m hungry and thirsty,” Em says.

“Didn’t you just have something?”

“I dunno. What was it?”

“I dunno. Can’t remember.”

“Exactly. I think that’s chai. You want some chai?”

“I’m not sure how the chai is settling with me. Should wait a few more days. Anyhow, it doesn’t look clean.”

“Let’s go.”

Asking of sorts. Not really. She’s likely low on blood-sugar. Seriously. She is a Type 1. The men have not moved, not an eye. We cross the empty street on this side of the chaotic intersection and when we’re standing up against the counter, they give us a smile and say, “Chai?” I’m still thinking. At least they asked. A cabbie on break or getting ready for an early start decides to help the chai man behind the counter. One flimsy shot cup is filled. That’s Em’s. She takes it, doesn’t wait for formalities, tips it up--part way. It’s steaming. Almost too hot to hold with bare hands. She blows over it. Her impatience gets the better of her and she throws it all to the back of her throat. “It’s goooooooooood,” she croons.

The cabbie waits for me. We eye one another and we both know that I can no longer resist. He fidgets with the Babel tower of cups and one drops into the wet and germ ridden sidewalk. He bends down to snatch it up and as if I hadn’t noticed he uses it to reinforce another cup to which my chai is poured. I think he smiles, a crooked old man smile. I squint back but thank him nonetheless. And somehow we both know that there are no innocents beyond the age of three.

Eff it. Down the hatch.

Oh. My. God. This shit is GOOD. Seriously good.

“How much?”

“Ten rupees.”

Done and done.

Wait. Did the cabbie take my money or the chai wallah?

08:18am

Bombay hopscotch. There's no sport more dangerous than crossing the street in India. We’re dodging sleeping dogs, cows, chickens, puddles, rickshaws and buses, and people and more people. It’s dry, or, drier now. I face Em. “Have you seen any tourists?”

“No,” she says straightly. “Just us.” Her mind is fixated on the next composition.

“And …?”

Down another street in another direction men stand around a cart on the side of the sidewalk boiling water. Empty clear-blue jugs of water. Like sky. But from where? We become part of the circle. The chatter doesn’t fade. On the sidewalk men from the store (what kind, I have no clue) notice us and doesn’t seem to care.

Perfect timing. The water in the pot is rolling, boiling. The man dips a cloth wrapping the contents of a fist-sized ball of chai. It looks to have been in use for years and without a break. Once I knew of a hamburger hole-in-the-wall where the secret ingredient was the grill of twenty years that had never been exposed to that dirty practice known as cleaning.

The man is concentrating. He speaks to none because this street ritual must attain exacting temperature and his preformations must become real. Use your formulas and measuring cups and deally-dabs in your fancy aluminum-brushed kitchen, but out here, in home turf, we use instinct and righteous judgment and experience. Amid the chatter they look askance at the chai man as if to say What’s taking so long? Is it ready yet? I need my cardamom and caffeine.

Em is already yapping it up with a few. I realize they don’t speak the same language, at least verbal. Just gestures and smiles and everything makes perfect sense more perfect than poorly choiced words. Someone beside me points, “Coffee?”

“Ah. Nah. We just had some … chai?” I point back down the street and mime nursing a scotch on the rocks, slowly tipping, sipping. “Thank you, though.”

“No no no. Coffee.” He tilts and bobs his head in that way that confounds a simple yes and no.

“Uh. No thank you. Chai. We just had it.”

“No. Coffee,” he points again, as if his crooked fingers could make the coffee or chai any clearer.

The chai man removes the rag of brown. He skims grind or leaves from the surface of the bubbling waters. Long metal ladle sinks to the bottom and comes back up to divvy between the three and then five or so glasses. Efficient if a bit messy. When the drink lines are nearly as tall as the glasses, he reaches down with one hand and fetches up the glasses with one finger in each glass like spokes of a chai wheel. What amazingly sticky fingers. Again, efficient, but incredibly messy. Each man finds renewed focus. They each take their turn. They drink their chai. The one beside me has his now and pushes it into my face.

“Coffee,” he says again and follows up with a come hither of his brows.

I smile as sincerely as I can and politely wave it off but thank him profusely. I watch him savor. All the while, I think: sticky fingers, sticky fingers.

08:40am

I’m standing on the median waiting to wave down a rickshaw but they don’t seem to venture into this neighborhood. I spot only taxies. Em is across the street taking portraits of construction workers in their hard yellow hats. There were three of them at first but now are fifty, but there is still just one of her. She’s laughing and won’t stop and I have no idea as to why. In the pictures they look serious as if they want to stone her but if you saw it they were just trying to look good and serious for the camera.

I lean back and look upward. Sketchy low clouds. A short time before we had found the coffee or chai stand on the street, we were caught in the midst of a downpour. One by one, people joined our little nook beneath the wandering arm of a mangrove and the green eaves of a closed storefront. Pink, blue, yellow umbrellas sprouted for those that found no surer cover. The rain came. It fell hard. For a time, it was the only thing heard, blocking out the thrum-thrumbing of traffic.

There on the side of the road, a skinny young driver in shorts deliberates with an older, more rotund one. The veteran seems to have won. A vacant face says that he has seen his share of cuts and jabs back in the day. Mumbai mafia. He walks calmly into the eaves with us. As the monsoon blesses and curses at will and at random, the apprentice polishes the taxi with a stained rag as the heavens above Bombay continuously sheds curtains and waves.

Story by HVH